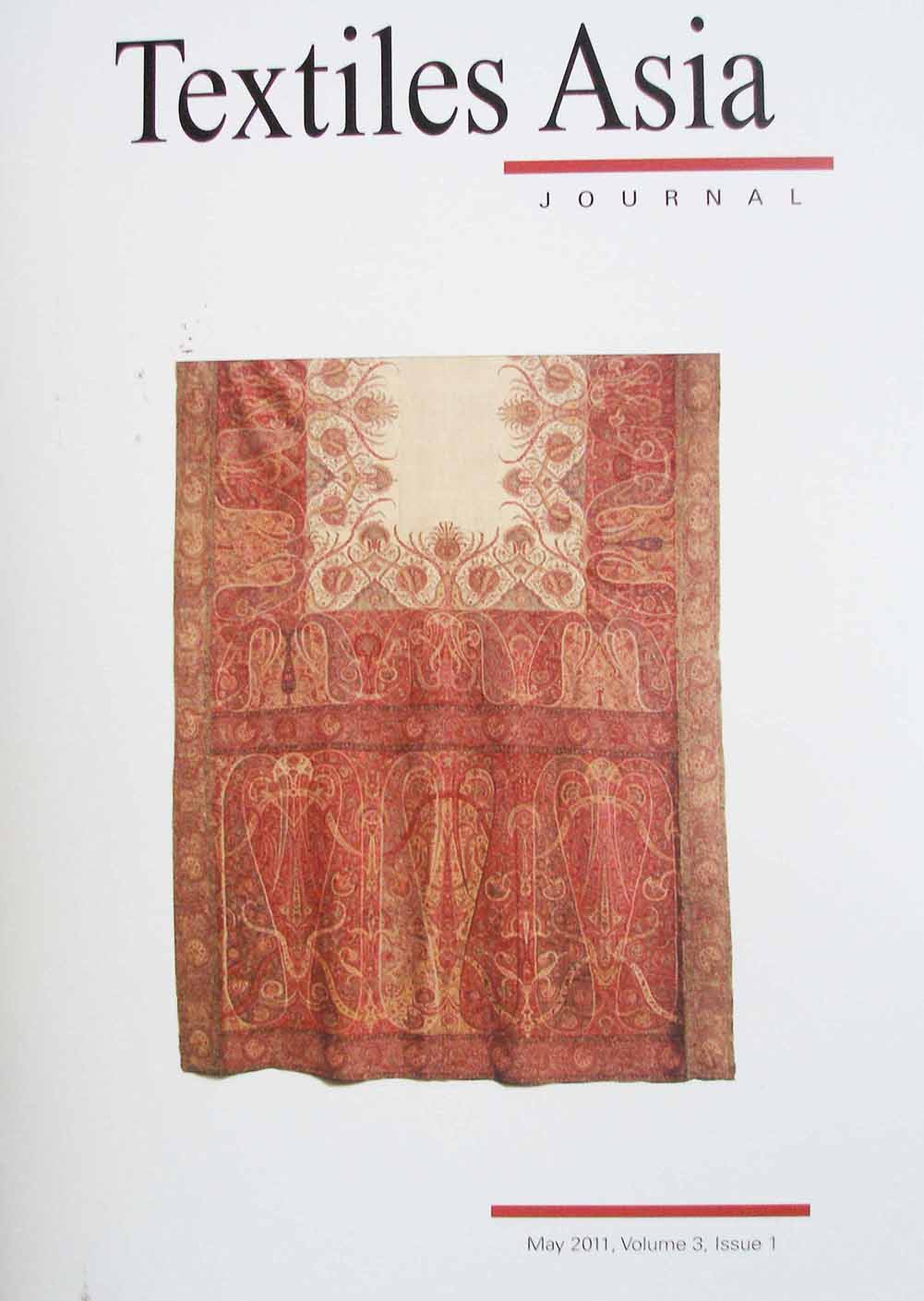

Khalsa and explosive Graphics in the age of Maharaja Runjit Singh’s Kashmir. Textiles Asia, May 2011, Vol. 3 issue 1

By Frank Ames

23 Oct. 2010

Located just under Kashmir in Northern India, the Punjab encompasses a five-river region that was severely battered by the opposing forces of various nations and religious sects during the eighteenth century. Afghans, Mughals, Sikhs, Pathans, Marathas, Rohillas and eventually the British, all clashed over this piece of land the size of France. Out of this warring chaos, the Sikh rose victoriously under the leadership of Maharaja Runjit Singh, who annexed Kashmir in 1819. During this time of Sikh ascendancy the Kashmir shawl, around 1820, underwent within a few years a dramatic change in both format and design, from a tradition of simple Paisley repeats at each end of a long swath of twill-woven pashmina wool, to one of dynamic, complex patterns that expanded over the whole area of the shawl. In this article an attempt will be made to show that a close correlation exists between these patterns and the artistic, religious and military environment that evolved under Runjit Singh.

For the first time in history, the numerous independent and quarrelling misls (chiefdoms) rallied behind a warrior and despotic monarch, Maharaja Runjit Singh, whose army came close to challenging that of British India’s. Within this landscape appeared a new pool of Kashmiri, Sikh and Pahari artists, developing an innovative vocabulary of patterns. Geometric shapes in the form of eight pointed stars, circles, spear-like forms, sweeping curves and architectonic devices- all of which intersected and merged in a rhythmic flow of what might appear as musical or at times pyrotechnic energy, began suddenly to permeate the shawl’s ‘canvas’ . Other curious objects entered this growing design repertoire such as the bow and arrow, quiver, boats, quoits and the dagger, the last of which is indubitably one of the five symbols of the Khalsa (Sikh Brotherhood). Frequently integrated into the shawl’s twill-weave (kani) were gurdwaras (Sikh temples). No longer limited to the shawl extremities, these various motifs began to fill the complete space of the shawl, to such an extent that hardly any area remained unadorned.

From what source did this new artistic expression of the Sikh period spring? Did it come from the sacred literature of the Sikh, such as the illuminated or illustrated Janamsakhi or the Sri Adi Granth? Was this expression absorbed by artists who remained close to Maharaja Runjit Singh’s Lahore darbar (court)? Was it initiated by Imam Bakhsh Lahori, one of the most sought after Punjabi artists of the period? Did these creative impulses filter down from the Pahari princely states as a result of Raja Sansar Chand’s submission to Runjit Singh? Or, perhaps it descended from the legacy of the Pandit Seu family of artists from Guler. Were they created in Lahore by Muhammad Bakhsh Sahhaf’s workshop or in one of the many other important ateliers that thrived in Lahore? The foreign military commanders, or mercenaries, who trained Runjit’s special forces (Fauj-i-Khas) may also have influenced these stylistic impulses with their regal battle costumes, war decorations and the flashy military accoutrements of Runjit’s Napoleonic Generals, Allard and Ventura, who arrived in Lahore in 1822. Unquestionably, the exotic novelty of this scenario generated awe and excitement among the weavers and craftsmen, who were sensitive to and actively engaged in the integration of colorful and artistic ideas into the fabric of their designs. In the thirty-five years I’ve been involved with the Kashmir shawl, these questions have continually piqued my curiosity and it’s the main reason I had set about writing Woven Masterpieces of Sikh Heritage, which endeavors to survey the most exciting examples from this era, and establish and weigh their importance as a mirror of Sikh culture.

William Moorcroft, more than any other early traveler into the Valley of Kashmir, is credited with the most complete description of the Kashmir shawl industry. During his long sojourn in Srinagar in 1823, only a few years after Runjit Singh annexes the valley, Moorcroft encounters a very curious shawl. Its borders (hashias) are called in Kashmiri “hashiyadar kunguradar”. He writes: “This has a border of unusual form with another within side, or nearer to the middle, resembling the crest of the wall of Asiatic forts furnished with narrow niches or embrasures for wall pieces or matchlock, whence its name.” Indeed, a few extant shawls confirm Moorcroft’s observations, which represent the first inkling of kani architecture and a radical change in the winds of shawl fashion. By 1830, the shawl ‘canvas’ had become an esoteric playground for an exotic mélange of geometric, architectonic, sweepingly curved, oblong and bizarre shapes, jostling with each other in seemingly mysterious ways.

My first book (1986) set forth an historical classification of this subject, which by highlighting socio-political segments of history, had identified and associated these graphic enigmatic patterns with the powerful expansion at the beginning of the 19th century of the Khalsa movement. However, my research was limited to much fewer shawls as compared to the number and diversity of those recently added to world collections. The big difference in the treatment of the subject between my first book and Woven Masterpieces of Sikh Heritage is that in the former Sikh association had been lightly touched upon and presented only as a plausible theory. Now, based on accumulated evidence, it is possible to establish with a reasonable degree of certainty that this style of Kashmir shawl is indeed a woven product illustrating the integration of symbolic ideas, architectonic concepts and contemporaneous events drawn from the Brotherhood of Sikh culture and the Land of the Five Rivers, the Punjab.

The high, or quintessential, Sikh pattern comprises overlapping images expressing a multiplicity of complex links and possible metaphors, many of which still beg interpretation. Moving into Euclidean spaces and isometries (one space embedded within another space) we find that the Kashmiri shawl arrives at a crossroads where the paths of simplicity, orderliness, and purity of line coalesce with the complexity of a new pictorial language filled with layers of interlocked graphic symbols. Previously, there was nothing to interpret, intellectualize or shake our sense of equilibrium. In the earliest of shawl patterns, the Mughal weavings, for example, we can easily connect with and marvel at the grace and poetic sway of flowers and blossoms. Indeed, they were a simple extension of the pervasive Mughal style defined by the swaying triple flexion (tribhanga) grace of floral shrubs found on carpets and in miniature and wall paintings, woven into costumes and sculptured on architecture. It was a powerful style representing the infusion of Persian and European iconography into a creative and indigenous Indian heritage. During the Afghan rule of Kashmir, the shawl continued its reputation for the repetition of the boteh across it end panels, its shape delimited by a bulbous curvilinearity in which it would appear that artists competed with each other to see how many different ways flowers could be arranged within the boteh’s strict outline limitations.

In Kashmir’s Runjit Singh period the student of Indian art, and the Kashmir shawl, must come to terms with a definition of Sikh art, which does not possess an easily definable style. Rather it is better understood as a synthetic phenomenon of artistic energies that colored the landscape of the Punjab-Jammu-Kashmir-Pahari region. Runjit Singh was no Jahangir. If he had a court atelier it certainly was not on a big scale. There were no genius artist such as the likes of Manohar or Mansur. There were no beautifully rounded faces with well-proportioned physiognomy, nature studies, or explorations of three-dimensional effects. Runjit Singh had neither the poetic sensitivity nor the artistic passion to become involved in such indolent pastimes; he was too busy fighting wars. Under his rule, Sikh art, if there is such a thing, most likely growing out of a need for Sikh mss and their illumination, of which Runjit was known to gift many sumptuously illuminated copies.

During the last few decades a renewed interest from the days of Archer’s seminal publication PAINTINGS OF THE SIKHS (1953), has developed, notably with the research of B.N. Goswamy leading the way. Three major exhibitions on Sikh art were held in the last ten years alone (fn), comprising paintings, coins, metalware, textiles, and armaments, which gave evidence not necessarily of an all encompassing Sikh style but rather as representative of “a new function, which must be considered with style as hallmarks of the art of the period” as proffered by Barbara Schmitz. Because of the lack of any unifying Sikh style, the weighty catalogues of these major exhibitions were copiously illustrated with craft objects which are merely ethnic artifacts and utilitarian items typical of contemporaneous Punjab., but not in themselves identifiable as Sikh works of art.

To know Sikh art, is to be familiar with the Sikh holy scriptures. These are the Sri Adi Granth Guru Sahib and the Janamsakhis. While the Granth is basically the Bible of the Sikhs, the Janamsakhis are stories about the life of Guru Nanak. Both of these scriptures during the late 18th and 19th century experienced an artistic renaissance, rendering them through illumination and illustration excellent sources of Sikh iconography as well as providing possible clues to the study of the Kashmir shawl.

Setting aside illustrations of the Granth and Janamsakhi, Sikh art as a style is difficult to define. The fact is that until the mid-19th century, Hindu and Sikh religions tended to meld together. It was customary for Hindus as well as Sikhs to pay homage to Sikh shrines and holy places. Dr. B.N. Goswamy, states that there is a “clear lack of any sharp demarcation between Sikh and Hindu themes when [especially] one examines the evidence of the murals on the walls of the Sikh royal palaces and other structures.” There was deep respect the one for the other. The Granth is filled with poetic commentaries (albeit brief) on Hinduism, Islam and Yoga as well as on righteous living. It is written in the form of devotional hymns and devoid of essential narrative; illustration was left basically to portraiture of the Gurus. It has been opined that this may be one reason why textiles and crafts of the period have no references to Sikh spiritual ideas.

The Granth’s 6000 shabads or verses are written in a poetic style and each of the hymns follow a specific raga style. Through them we learn that Guru Nanak must have been very closely connected to workers in the dye industry for ‘dyeing’ is repeatedly used as a simile and metaphor. “The Lord dyed in deep red; the Lord is an expert dyer; He who has been dyed in the red is of great good fortune; dyed in fast color, the color that never fades” are only a few examples of Nanak’s obsession with the color red.”; “dyed in the divine, …the lord dyed in deep red; the Lord is an expert dyer…;; He who has been dyed in the red is of great good fortune; dyed in fast color, the color that never fades. My mind is imbued with the Lord’s Love; it is dyed a deep crimson”. While red was certainly a popular color, green seemed to be the preeminent hue among Sikhs, and saffron, a color sacred among Hindus, especially.

In Nanak’s morality of sartirical etiquette, we find “Truth and charity are my white clothes; the blackness of sin is erased by my wearing of blue clothes, and meditation on the Lord’s Lotus feet is my robe of honor; contentment is my cummerbund…; dressed in vermillion you will be happily wedded should you take the name of the Lord; O Baba, the pleasures of other clothes are false, wearing them, the body is ruined, and wickedness and corruption enter into the mind.” Turning to the hunt and the warrior’s paraphernalia, the Granth states “The understanding of Your Way, Lord, is horses, saddles and bags of gold for me; the pursuit of virtue is my bow and arrow, my quiver, sword and scabbard ; to be distinguished with honor is my drum and banner.”

While much of the above information on dyes and clothing may be important for the textile scholar, still we find no mention of shawls, despite the fact that Guru Nanak actually was born near Lahore and married in Batala, a village whose main artery led to Kashmir

The Janamsakhi is, contrary to the Adi Granth, filled with anecdotes of Guru Nanak the most popular being Nanak’s wedding; his sleeping at Mecca with feet pointed towards the Qaba; or Nanak’s lying under a tree with his head shaded from the sun by the hood of a snake. Nanak’s ever present sidekicks, Bhai Bao, his devoted follower, and Mardana, the rabad player are two individuals who usually always figure in miniature paintings of the Master. However, even here we find that in other than painting there is nothing that carries over into the crafts. This lacuna can be contrasted with some 19th century kani weaving in which we can observe figures of Krishna and Radha. It is not until the later part of the 19th century, beyond our focus of attention, that Sikh themes from the Janamsakhi, life stories of Guru Nanak become prevalent.

During this stage of Indian history who in fact were the key players in patronizing the arts? Lahore bustled with activity under Runjit Singh. Building was at a frenzy. Among the many book sellers, Muhammed Bakhsh Sahhaf was one of the biggest. He was also an artist in his own right as well as a good friend, if not relative, of the equally renowned artist Imam Bakhsh Lahori. Sahhaf’s illustrated and calligraphic books reached clients throughout Indian and Iran. Although the Ahluwalia, Majithia and Sandhanwalia misls were commissioning works from painters prior to the 19th century, these Sikh families were now powerful players in the world of Runjit Singh’s hegemony of Northern India and continued to actively commission works of art. Runjit Singh and his bevy of European officers, such as the Generals Allard and Ventura, were continually engaging mural painters to decorate their palaces, gurdwaras, public buildings and homes. Last but not least among the many patrons of the arts, were the powerful Dogra Brothers, Gulab, Suchet and Dyan Singh, who worked very closely with Maharaja Runjit Singh. Many of the artists came from Kangra, which was ruled by Raja Sansar Chand. A serious connoisseur and avid collector of miniature painting, Chand had lived in a dream world of royal opulence which came to a sudden end in 1809, when Kangra fell under the sway of Runjit Singh. Many former Kangra artists were now plying their trade in other hill state regions and in Lahore, Amritsar, etc.

Indeed, it is from a Kangra painting that a major discovery in shawl iconography came about. (see illus.) In this painting the body of Maharaja Runjit Singh is laid out on a bier while seven of his slave-girls mount the pyre to commit sati. In the corner a boat dripping with garlands and appointed with flags lies on a bier across a beam placed stern to bow. Years earlier I recalled a kani shawl I once owned having a very odd motif. It turned out that that motif matched the boat in this very painting, replete with all the decoration. The boat as well as the bow and arrow mentioned above, with all their interpretations went on to become a very popular motifs in Kashmir designs.

All this to show the extent of the fertile artistic landscape that existed in Northern India at the time of the Kashmir shawl’s new ‘awakening’. But in no way should one assume that this awakening happened in Srinagar. Runjit Singh may have annexed Kashmir 1819, but certainly Sikh culture was not an influence there. Apart from the controlling brigades of Runjit Singh’s forces, Sikhs hardly lived there. The Punjab was there home, where 12 misls basically controlled the region known as the Land of the Five Rivers (i.e. East of the cis-Sutlege) with Lahore being the focal point, the darbar, the royal throne of power. However, Jacquemont observed that noble sardars kept their own shawl ateliers in Srinagar, insuring that a steady supply of high quality shawls were always available. Similarly Lahore, it would appear, harbored large shawl weaving ateliers, as evidenced from a series of fine Company style paintings made at the time of the Universal Exhibition of London in 1867. Whether the Sikhs ran such ateliers prior to Kashmir’s annexation is not wholly clear but a good guess would be yes.

Because of the severe Indian climatic conditions and early India’s neglect of conserving important archival material, for the textile scholar, many pieces of the puzzle are still missing. Jeevan Singh Deol, eminent professor of Sikh studies, further points the finger to the fact that so many “extant illustrated texts depicting Sikh themes or commissioned by Sikh patrons have experienced a broad geographical diffusion” rendering them extremely difficult to access. And in many ways he sums up the frustration that many of us feel, in the conclusion to his seminal article, Sikh Scriptural Manuscripts: “In a very real sense, then, illustrated and illuminated Adi Granth mss are a window into a lost Sikh cultural universe. Their disappearance marks a major change in notions of cultural prestige and attitudes toward the physical form of scripture. At this stage of research, we know regrettably little about the geographical, temporal and social distribution of adorned mss and even less about the patrons, scribes and artist who created them. Until this changes, it will remain extremely difficult to understand the multiple meanings and intentions that lay behind their creation and use.” (p.43)

It is hope that in this brief space the above will have provided the reader with a glimpse of the complex forces operating under Runjit Singh, and illustrated how the Kashmir shawl became for the first time a kind of ethnographic mirror of a dynamic culture unique to India’s Punjab.