A Kashmir Paradigm Shift : Qajar and Zand Painting as evidence for Shawl Dating

Zand Painting by Muhammad Baqir, 1778

The following article is the original manuscript sent to Hali Magazine for the March 2005 edition. Because of the unfortunate and misleading changes the editors had made in the text, it was deemed necessary here to published the unedited version, which should clarify any of the faux pas ‘corrections’ performed by Hali.

Because of the detailed nature of this essay, and to obtain a good understanding of the variations in design motifs, it behooves the reader to refer to the illustrations in Hali(issue 139, March-April, 2005).

Curiously, Sotheby’s recent sale (1) of a new unpublished Zand (1747-1779) painting, “A Portrait of a Dancing Girl”, makes no mention of the magnificent Kashmir shawl that figures with such dynamic impact in the picture. Signed and dated Muhammad Baqir, 1778, the shawl’s seemingly late pattern seems to clash with the early date of the painting. This shawl cannot fail to rivet the attention of textile experts and shawl aficionados who have carefully followed with keen interest the early development of the shawl’s boteh. Not knowing the painting’s date, those familiar with shawl iconography would not hesitate in dating its pattern to the first quarter of the 19th century or even more precisely to around 1815. Over twenty years ago, I first noted that the only known 18th century pictorial evidence for the curvilinear boteh was a painting in Toby Falk’s Zand Painting, titled “A Girl Playing a Mandolin”, signed Muhammad Sadiq and dated 1769-70(2). It features a woman in pants with a sharply defined, unmistakable Kashmir boteh pattern.

With the impending publication of my book in 1986 (3), the daunting thought emerged that many of the Kashmir shawls woven prior to the Sikh period (1819-1839) might have to be quickly reassessed. Such a dramatic volte-face in chronological thinking would have certainly raised a few eyebrows. Since this was the only known painting of its type at the time, located in a private collection in Tehran, and thus couldn’t be easily corroborated, I had somehow convinced myself that given the obviously ‘late’ motif of her pants, the date inscribed on the painting was either inaccurate, misread or possibly bogus. I was wrong.

It wasn’t until 1998 when Layla Diba’s magnificent book Royal Persian Painting (4) appeared that I began to have serious doubts about current shawl dating. Diba had revealed another chronologically ‘unsettling’ painting of a similar date and artist, as that one in Toby Falk’s book. Having consulted Diba about the Falk painting, she assured me that both signature and date were clearly inscribed on “A Girl Playing a Mandolin”(5). Suddenly we now had three 18th century Zand paintings with kani material of sharply defined, strikingly ‘precocious’ botehs.

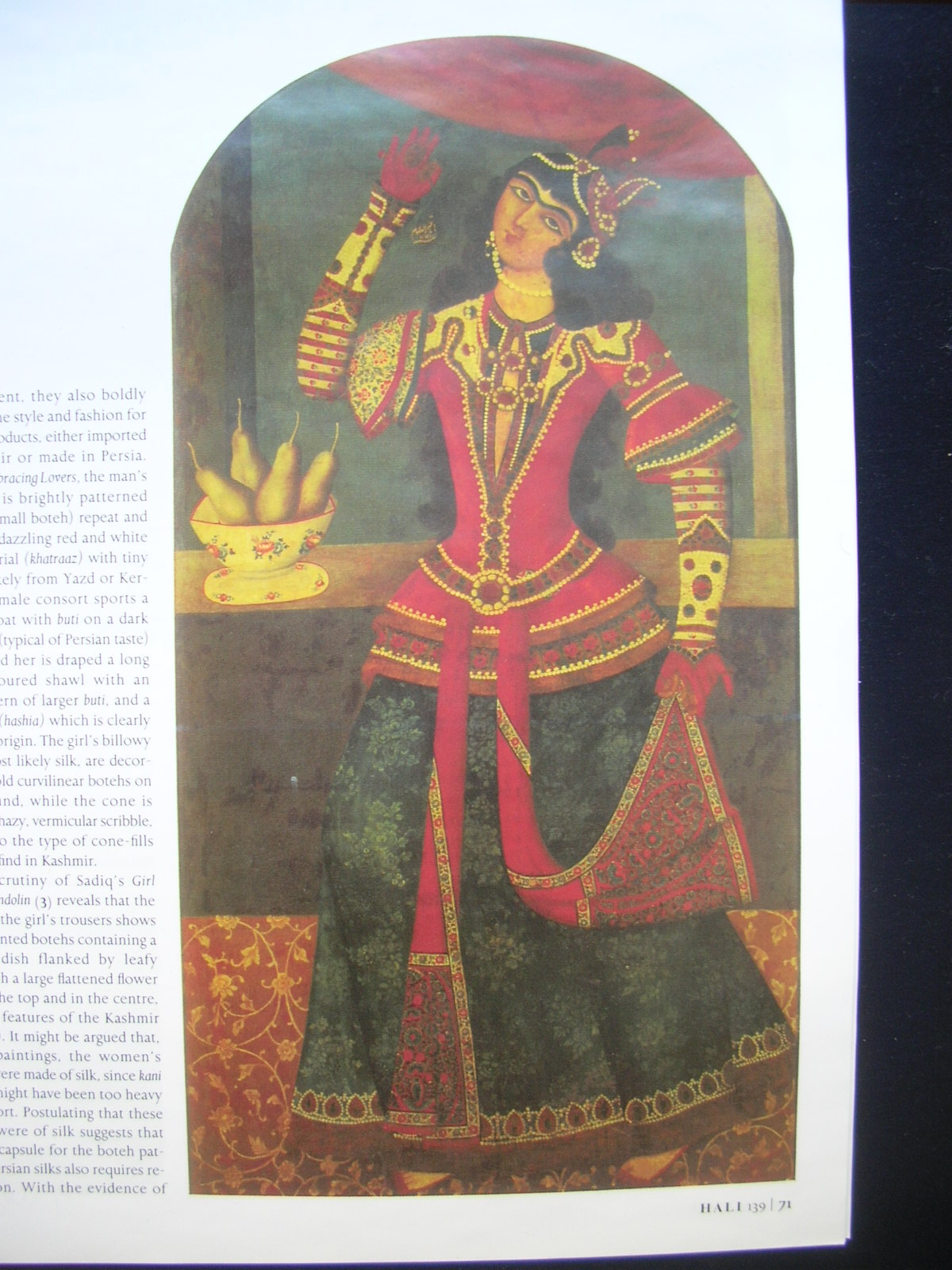

Although the painting in Diba’s book entitled “Embracing Lovers” is not signed, she firmly attributes it on a stylistic basis to Muhammad Sadiq (fl. 1740-1790), with the date of 1770-1780. While all three paintings represent an emblem of courtly luxury and refinement, they also boldly pronounce the style and fashion for Kashmiri products, either imported from Kashmir or for those made in Persia. Indeed in “Embracing Lovers” , the male’s tall red cap is brightly patterned with a buti repeat and his coat is a dazzling red and white striped (khatraaz) material with tiny buti, most likely from Yazd or Kerman. His female consort sports a ‘Kashmir’ coat with buti (small botehs) on a dark blue ground (typical of Persian taste) while behind her is draped a long saffron colored shawl with an overall pattern of larger buti and bordered by a hashia which is obviously of Kashmir origin. The girl’ billowy pants, most likely of silk, are patterned with bold curvilinear botehs on a blue ground, while the cone is filled with a hazy, vermicular scribble, something very unrelated to the types of cone-fills, one would find typical of Kashmir.

On a stylistic basis, Diba attributes this painting to Muhammad Sadiq, the same artist of “A Girl with a Mandolin”. Scrutiny of “Mandolin” shows that the pant’s pattern clearly reveals sharply pointed botehs containing a vase and dish flanked by leafy fronds and a large flattened flower placed at the top and in the center, all typical features of the Kashmir pattern. In addition, a long shawl is obscurely draped behind her, but due to the lack of a proper color photo, little can be deciphered. It might also be argued that the women’s pants in both paintings were made of silk, since kani material might have been considered too heavy for comfort. Postulating that these pants were of silk suggests that the time capsule for the boteh pattern in Persian silks equally requires re-evaluation. With the evidence of these paintings, both silk and kani boteh patterns appear to be in fashion. A distinct likelihood that the silk industry of Persia was first responsible for the creation and dissemination of these boteh curvilinear patterns should not be overlooked.

The contribution of Persia to the kani (double inter-locked twill tapestry wool weave) shawl industry has remained in almost complete obscurity for a long time, often eclipsed by the world famous industry of Kashmir whose kani products were almost always considered superior (6).

Kashmir shawls are so well identified and defined by the shape and style of the boteh pattern, that it influences most collectors, curators, and aficionados to date pieces according to these ubiquitous patterns of repeat design.

Although the development of the boteh has been previously discussed at length (7), the ability to develop better chronology for its development has often been hampered, surprisingly, by lack of pictorial evidence from India. Until recently, the earliest Indian paintings found, in which, one can say for sure, that the shawl has been well replicated with its distinctively identifiable features, have been from the first quarter of the 19th century. (8) While 18th century Indian paintings certainly contain many instances of the Kashmir shawl, the detailing is so sparse and undecipherable, that the pictorial evidence barely resembles the extant evidence (9).

In the Western world, one had to rely on the Empire painters such as Ingres, Baron Gros, Godefroy, and David who meticulously featured the Kashmir shawl in their paintings. One can also turn to see designs of French printed textiles in an album, from the Oberkampf estate, bearing the inscription: “Most were copied from the first shawls and scarves which were introduced in France at the beginning of this century (c1800) by the officers of the Egyptian army.”(10)

In the Near East, the early Qajar period (1795-1834) of painting, more than any other contemporary period, is replete in shawl illustration. Qajar nobles reveled in Kashmiri cloths. The types of patterns they enjoyed most, appear to be narrowly focused on either tiny buti repeats or on the curvilinear boteh. Thus, Qajar painting appears to act more as a confirmation of Persian fashion and rather than as discovery of new stylistic information. Therefore, before c1800, until the discovery of these three paintings, there was basically no pictorial evidence, either from Western or Oriental painting. Looking at extant shawls themselves, held by institutions and collectors, there are basically no dated shawls either from this period or earlier. (11)

Evidence of the curvilinear boteh developing well into the 18th century, as attested by Baqir’s “A Portrait of a Dancing Girl”, serves to confirm the pictorial legitimacy sought by textile historians.

Although life-size Persian painting began in the 17th century, its popularity, it seems, emerged only at the beginning of the 18th, reaching its peak with Fath Ali Shah (r.1798-1834) in the 19th c.

Baqir’s “A Portrait of a Dancing Girl” depicts a woman with a wonderfully detailed long Kashmir shawl that has been wrapped around her waist and tied in front around her belt buckle. As she pinches one end up with her castanets, the other falls down in a smooth telescopic twist with the pattern clearly visible.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the dochalla’s (long shawl) hashias (borders) were extremely narrow and comprised of a finely laid out floral meander of usually less than four or five flowers, flanked by an insignificant guard border whose width was no more than a few millimeters. After the first decade of the 19th century, this was to change by a widening of the hashia with more evolved guard borders. (12) Baqir’s meander shows only a two flower repeat within the typically narrow border of the 18th century.

However, one should be careful not to confuse patkas with dochallas in that the former almost always have larger hashias. Baqir’s botehs are sharply curvilinear and filled with flowers that are not simply mosaic in style, but exhibit clearly identifiable features from the known repertoire of Kashmir designs. Baqir’s enthusiasm for the shawl, though not as meticulous in his details as, say Ingres’s, is nevertheless such that he leaves us little doubt as to the shawl pattern’s floral content. Although close in format, but not in detail, the boteh does resemble those found in Moorcroft patterns dispatched to England in 1822. (13) However, Baqir’s boteh is clearly from an earlier generation in “Dancing Girl”. There is a large blossom at the top, while at the bottom, we find, flanked by leafy sprays, a vase spewing forth the familiar flower buds and blossoms. More surprising yet, for this early date, is the fact that the boteh is tightly enveloped by a similar dense thicket of flowers, which mimics the boteh’s interior, and which covers most of the red ground.

These three key paintings by Sadiq and Baqir represent an important milestone in shawl history. Whereas, many of the life-size portraits symbolized a form of political propaganda, it appears that others such as these three were destined to make an important fashion statement about Kashmir shawls. The exciting revelatory boteh graphics they depict seem to instantly overthrow all our previous ideas of chronology for the shawl by at least thirty years, establishing a new time-line paradigm. The implications are huge and suggest the possibility that the curvilinear boteh first developed in Iran.

For a long time, it was felt that this curvilinearity of the boteh had evolved not much before the turn of the 18th century, and even then, not in any popular manner; yet, in fact, here was dated proof to the contrary. The appearance of these ‘Sadiq botehs’ becomes, at this point, quite compelling for re-assessing shawl dating and requires us to take another hard look at the types of designs made popular not only in Persia but also under Napoleon, or those designs which go under the eponym ‘Empire” shawl. Thus far, apart from pallas of tiny buti, 18th c. French paintings illustrating Kashmir shawls with ‘full blown’ botehs are unknown.

Does this mean that many of the shawls with this type of design that have been previously dated to 1815-1820 now have to be reconsidered? The immediate answer to that question is “yes”; the long-term answer will take, well, a little longer. Why? There are other factors to be understood. We need to look at the dyes used, the botanical rendering of the boteh, and we need a thorough knowledge of the hashia pattern repertoire of the Afghan-Sikh period. In addition, much as a painter’s brushstroke can identify the artist, the outline shape must be carefully weighed against the floral naturalism of the content. The effect of all this is to narrow the playing field, placing a heavier demand on the researcher to be more precise in shawl pattern recognition.

Despite the long history of Persia competing with Kashmir to produce a fine shawl, there is no convincing kani evidence for Persian products of the 18th century. Almost all the beautiful long shawls, jamawars (long gown shawl) and moon shawls we know of, attributed to this period are from Kashmir. 18th century shawls possess a distinct color palette of rich and exotic hues and unique botanical details, and, so far, none attributed to Persia have been found with these characteristics.

At present, we don’t find the typical Indian patka with its wide hashia format in Zand or Qajar painting. Conversely, we don’t see fine Safavid silks with botehs in 17th century Iranian paintings. Safavid kani shawls, where one might expect to at least see designs with the bird-and-tree-stump cliche, appear to be non-existent. What is important to note from all this is that despite Iran’s rich textile industry, where once great artists such as Shafi Abbasi and Muhammad Zaman flourished, transitional elements that might link typical Safavid designs to those found in the kani shawl appear to be patently missing.

The impact of Persia’s silk or kani fashion on the products of Kashmir has yet to be fully investigated. In Moorcroft’s trade/commerce notes (1822), Persia tops the list as recipient of the highest percentage of different shawl items exported from Kashmir. Thus Persia’s mercantile influence should be weighed when considering its impact on Kashmir and the possible introduction of the Zand boteh into the repertoire of its shawl industry. We also know from traveler’s accounts to Kashmir that the shawl industry was in the hands of just a few rich Persians. Jacquemont talks about the commerce of Kashmir with Tibet as being in the hands of Persian shias (14).

While the 17th to early 18th century Persian paintings are devoid of Kashmir shawls, patkas are clearly depicted, although most likely woven of silk. It’s only when we approach the Zand period that we come across small patterned kani dress accessories and the transfer of the decorative motif of the shawl. The curvilinear boteh appears on women’s pants and jackets, and in men’s turbans and waistbands, according to the visual evidence the figural paintings afford.

Tiny patterns or butis were usually the best choice for the Persians, because their fashion dictated that these cloths be wound and twisted as men’s turbans and waistbands. A large pattern would not have looked appealing as the design would have been broken up and lost in the folds. Wrapping a classic Zand high turban was different; dochallas were often used, making good use of the long hashias as decorative swirls while the pallas were mostly hidden except, on occasion, one could glimpse part of a tall boteh. (15). The approach of the Qajar period, which paralleled the high Sikh Period in India, seemed to bring about a radical change in fashion, as evidenced by the wide spread use of the sharp boteh pattern on many other costume elements. This is especially apparent in the figural painting of nobles sporting long fur-lined robes, while in India a similar transference occurred except that the draping of the shawl still remained the custom.

The discovery of these three Zand paintings requires us to re-evaluate the origins and development of the boteh motif. The Persian silk and kani industry and its patronage should be carefully reviewed to develop a better understanding of the propagation of motifs within the historical complex of the international shawl industry. The paintings instruct us above all not to disregard fashionable patterns in the Kashmir shawl which remained in vogue for a conservative Persian taste, while parallel to that trend other fanciful motifs came and went, fulfilling a niche for the exotic and whimsical. They not only provide hints of a textile motif, the boteh, that could date shawls even to the early 18th century, but extend the implications for reassessment of the prior dating of rugs and carpets, as well.