CHRISTIES AUCTION – 9 Oct 2015

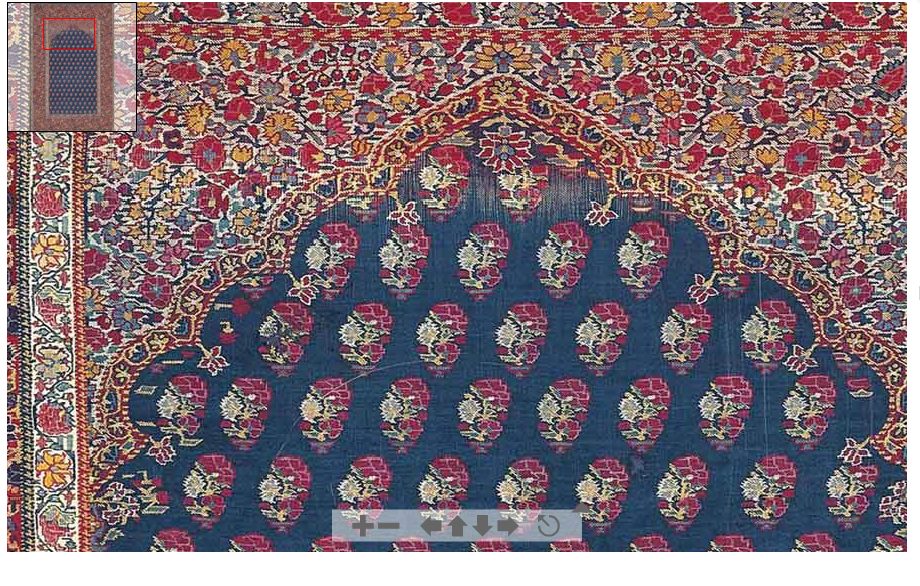

Lot 139 achieved a rightly deserved price. Highly collectible, these prayer niche types are usually woven all in one piece. At 28 x 43 inches, its compact size, lends it easily to displaying as a work of art and makes it a choice item for collectors of oriental rugs and Islamic art. But they also have a transcending, timeless quality that make them very appealing to people in the arts in general. The ‘stars’ diapering the midnight blue field gives it a cosmic feel.

The spandrels were not very well woven but the rest of the weaving glistens with bright blossoms and scattered racemes. Judging from the botanics of the flowers its age is definitely well into the 18th century, perhaps as early as 1750 or so. Whoever bought got a wonderful piece.

Recently a ‘new’ map shawl was discovered. Up until now only four map shawls were known to exist. While in many ways they all resemble each other insofar as they all depict the topology of Srinagar, each possesses its own embroidered charm of colorful tints and landmark embellishments of this famous city nestled at the foothills of the Himalayas. Although the V&A’s is the most widely known simply because it has been exhibited so often and published, the National Gallery of Australia’s is perhaps on par as far as workmanship, colors and technique of embroidery. The British Royal Collection owns the third but its rectangular format gives it an odd appearance and I have yet to view any details of it. Rosemary Crill published a not so appealing photo of it in Hali 67 (1993. The fourth is in the museum of Srinagar suffering a terrible fate of abandonment to the vicissitudes of dampness and heat and when I last visited the museum, way back thirty years ago birds were scooting in and out of missing windows!

Measuring 73 x 72 inches, basically square, it contains dozens of Persian inscriptions identifying the various gardens, lakes, buildings, mosques, etc. of the town. I’ve counted at least 15 different colored yarns but there seem to be many more depending on the subtleties of shading employed. Embroidered all in fine pashmina, the needle work is of the highest quality. It’s whereabouts unfortunately cannot at this time be divulged.

This recent discovery is a monumental addition to the what was up until now rather limited repertoire of such embroidered maps. Apart from Rosemary Crill’s informative article in Hali (1993) wherein she describes the V&A’s magnificent map shawl, no one has yet really done an in-depth study of them. Perhaps this new addition will find new eager scholars willing to undertake the task. Even without understanding the social context in which they were created, the complexities of the embroidery has yet to be analyzed by experts. I feel that the embroidery for each of the map shawls varies to some degree however this one is done in a true embroidery technique, not needlework like the V&A or Australia’s map shawls, a technique certainly involving more intensive work. To understand better this needlework, anyone with an early dochalla should take a close look at the kunj or corner field botehs which were always done with this technique. Usually it was done also with the dorukha technique where one finds the ground color changed from one side to the other, a kind of flat couching stitch.