Kani Shawl News

CHRISTIES ONLINE SHAWL AUCTION, 11-18 JUNE 2019

Some brief observations:

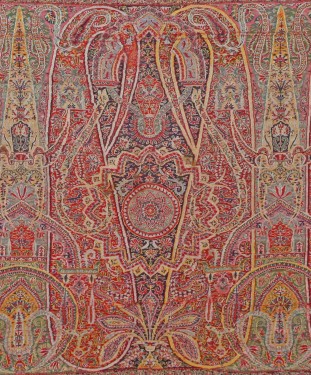

Eighty-five rare Kashmir shawls, formerly from the Sam Josefowitz collection of Switzerland, were recently sold at Christies’ online auction.. Historically and as a group, it was perhaps the most important sale of such items to have ever been put on the market. From the high Mughal period of the 17thcentury on through the Afghan, Sikh and Dogra periods, each of these eras under which Kashmir was dominated, found significant representation at the sale. Without question, la piece de resistance was the white ground, Mughal boteh fragment, lot 19, selling for over $90,000 (rounded off). However, at the top of the best seller list, was the kani mat, lot 17 which sold for an astounding $244,000. It was a small millefleurs-like weaving with a blue-ground central field, each of the corners with a quarter medallion, as in moon shawls though without the central medallion. Whether the bidders were aware of the extensive damage it had suffered and its lack of provenance, I don’t know but there was certainly nothing in its aesthetics, history to justify such a price. Lot 55, an embroidered rumal with figures, was the next unexpected big winner, selling for $53,000. Despite its rather shabby condition, large areas of wear, faded colors and extensive loss of embroidery, its fine artistry, painterly vegetation and early date, flickered and twinkled enough here and there to cause enough serious interest. On Lot 1, a fine dorukha its beauty and its excellent condition along with its solid wool foundation propelled its price to $39,000. Such numbers are not unheard of in India where appreciation of the dorukha has over the years driven their prices up, in some cases astronomically. The eye-dazzlingly black ground moon shawl (lot 4) with sunburst (shamsa) pattern was in my mind one of the most brilliant graphic designs ever to find its way into a kani rumal. It had been hanging in my living room for a few years before it found its way into the Josefowitz collection. What most are not aware of is that the black ground had been painted in. It took me the better part of a few hours working with various strength magnifying glasses to ascertain this fact. This just goes to prove how meticulous, of not ingenious, the weavers were. It was a bargain at $17,000. Setting price records again we turn to the Sikh period: two very nice, long shawls, quintessential specimens, one with imposing peafowls repeating across its pallu (lot 25, $27,500) the other squiggling with snakes and vines and complimented with an eight-leaf, white kani center of powerful proportions (lot 61, $32,500). The former, for sure, a product of the 1830s, the peafowl motif had been copied off Indian shawls by the well-known French manufacturer, Hébert in 1839.

The, late Sikh, zoomorphic long shawl in lot 10, was a masterpiece in weaving and deserved the hefty price paid for it ($28,500). Its design might have been the inspiration for the French shawl designer to initiate his famous jungle foliage patterns of 1848-1850. Featured in my book, WMSH, the rumal in lot 57, the pattern to which I liken it recalls the dizzying holographic effects of a spinning propeller, also set a record for a rumal ($32,500). As a work of art, it’s unsurpassed with nuanced tones and brilliant bull’s eye center. For the astute buyers, there were bargains to be had as well. Lot 62 ($12,000), a beautiful early 18thcentury jamawar, in great condition, replete with its original hashias and diapered pattern of excellently drawn buti flowers propped on a tiny mound. The red ground rumal in lot 84 ($3,000), in my estimate was at least as important as the ‘propeller’ one. There were three narrow stripped moon shawls -Sam loved moons shawls- all circa 1800 that went for strong prices, especially lot 83 which sold for $28,500. Lot 15, a complete dochalla from the 17thcentury, despite its fading, poor condition and weak design, hammered down at an surprising $53,000. However, buyers are aware these days that complete 17thcentury Mughal shawls have virtually dried up. Three other rumals (Lots 36, 43,45), aesthetically not much more than garden variety, drew paradoxically strong hammer prices: $9,000; $4,400; $4,400. They could have easily been ignored by collectors at $1,000. Lot 73, a finely wrought reversible (dorukha) rumal, c 1870, of which very few exist. It’s similar to a pair of them in the Cooper Hewitt Museum. This one went for quite a fair price of $20,000. Overall, the high prices attained sets the bar quite high for future sales, even if the majority of the buyers still remain anonymous. This sale is even more surprising given that Skinner’s Auction has, over the past decade, been the preferred place for dumping quantities of Kashmir shawls on a weak market where buyers have snapped them up unapologetically. Exception being a saffron ground, moon shawl selling 6 years ago for $65,000.

Care to comment?

Please reply via ‘contact’ page. Thanks

News

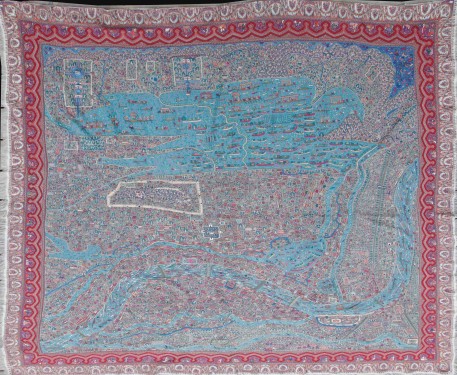

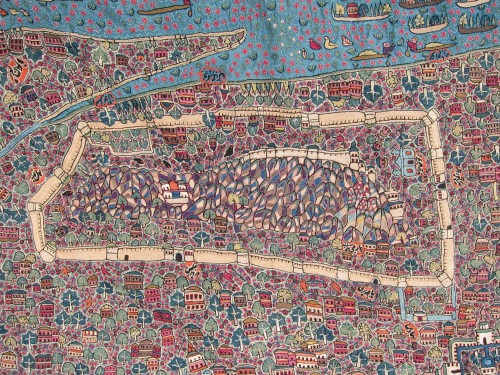

Embroidered map ‘shawl’ of Srinagar 72x72inches.

Recently a ‘new’ map shawl was discovered. Up until now only four map shawls were known to exist. While in many ways they all resemble each other insofar as they all depict the topology of Srinagar, each possesses its own embroidered charm of colorful tints and landmark embellishments of this famous city nestled at the foothills of the Himalayas. Although the V&A’s is the most widely known simply because it has been exhibited so often and published, the National Gallery of Australia’s is perhaps on par as far as workmanship, colors and technique of embroidery. The British Royal Collection owns the third but its rectangular format gives it an odd appearance and I have yet to view any details of it. Rosemary Crill published a not so appealing photo of it in Hali 67 (1993. The fourth is in the museum of Srinagar suffering a terrible fate of abandonment to the vicissitudes of dampness and heat and when I last visited the museum, way back thirty years ago birds were scooting in and out of missing windows!

Measuring 73 x 72 inches, basically square, it contains dozens of Persian inscriptions identifying the various gardens, lakes, buildings, mosques, etc. of the town. I’ve counted at least 15 different colored yarns but there seem to be many more depending on the subtleties of shading employed. Embroidered all in fine pashmina, the needle work is of the highest quality. It’s whereabouts unfortunately cannot at this time be divulged.

This recent discovery is a monumental addition to the what was up until now rather limited repertoire of such embroidered maps. Apart from Rosemary Crill’s informative article in Hali (1993) wherein she describes the V&A’s magnificent map shawl, no one has yet really done an in-depth study of them. Perhaps this new historic addition will find new scholars willing to undertake the task. Even without understanding the social context in which they were created, the complexities of the embroidery has yet to be analyzed by experts. I feel that the embroidery for each of the map shawls varies to some degree.

=====================================================================================================

To Sikh or not to Sikh

The Argument:

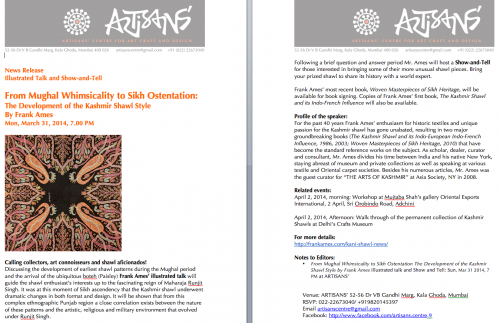

In my first book The Kashmir Shawl and its Indo-French Influence (1986), I had established a system of four categories or periods if you will that I felt helped define and classify the multitude of shawl patterns. Control of Kashmir during its four hundred year history of kani weaving began with the Mughals; Afghans, Sikhs and Dogra followed in succession right up until what’s considered the demise of the Great Shawl industry, about 1880.

In 2010 my second book came out, Woven Masterpieces of Sikh Heritage which delved much deeper into the evolution of style and the forces that shaped it under Maharaja Runjit Singh.

In my work I argue that a special shawl style indigenous to the Punjab came about that was based not on or necessarily influenced by European shawls. A style that found its roots in the fertile soil of the Punjab, an art style nurtured by the Sikh Brotherhood of the Khalsa movement and an autonomous culture that was in many way not part of typical India but isolated in a region cordoned off from the rest of the subcontinent by very specific boundaries, the Sutlej River (cis-Sutlej) where one side was ruled by the British, the other, the Land of the Five Rivers, by the Sikhs under Runjit Singh.

Nevertheless despite my work in this area, a few textile experts have expressed doubts. They feel that the Sikh style derived from European Jacquard woven shawls that had been designed by French artists; moreover, that most of the basic designs evolved before the Sikhs took political control of the Kashmir Valley.

In this essay my aim is to demonstrate the fallacy of this belief.

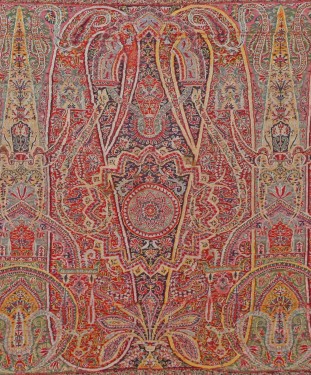

During the late 1820s and early 1830s in the Kashmir/Punjab region of Northern India a certain strain of bizarre patterns began appearing on the kani woven Kashmir shawl. This curious strain comprised geometric shapes of sweeping curves and arches, architectural devices that resembled indistinct buildings, blossom arrangements of pyrotechnic-like displays, skeletal botehs (paisleys) and stars and lobed circles indented with spear-like tree devices, recurve bows, quivers filled with arrows, shields, boats, and even daggers, to name a few. The confluence of these design ideas woven into the kani shawl is what I call in my publications the Sikh Kashmir shawl. Looking at the patterns, however, one’s opinion can only be drawn to a stark non plus since although the patterns are frequently awesome and majestic there is nothing inherent in their designs that could be equated with contemporary shawl designs being jacquard-woven in Europe. In fact, it is extremely difficult to equate them with any earlier form of known artist style or movement. The patterns are truly unique. However and despite any proof, there remain a few skeptics who refuse to align themselves with this train of thought. Their contention is that they see European influence as the driving force behind these bizarre patterns, that somehow Kashmiri artists were being exposed to shawl designs such as those being wrought by the well-known French industrial designer like Amedée Couder, or for example the Parisian manufacturers Bournbonet and Chambellan&Duché, and had set about copying them into their kani weavings in Srinagar.

But the European designs of the 1830s that illustrated architecture were also extremely fresh and new to the market. In fact, so novel were they that extremely few have ever been found. On the other hand, Couder’s Ottoman or Byzantine style Isfahan shawl of 1834 was frequently found woven as well as related patterns that imitated it to some degree. Bournhonet’s Gothic shawl ideas didn’t make it into ‘print’ so to speak until 1839(see p. 80 of MLS). All this to say that if these Gothic architectural designs were indeed so popular as the skeptics imply, then why is it that not one Indian Kashmir shawl has ever been found with a replication of these patterns for the Western market?

As a concession to the skeptics argument I will concede that it’s not impossible that a few of these Gothic Jacquard shawls had traveled to Kashmir where upon the local artists, not understanding the complexity of the designs nor the social implications of the church-like architectural structures, set about creating their own “Gothic” style. But wait: The skeptics continue to decry that these “Sikh” period shawls were for export! So here lies the fallacy of their argument. Export markets exist only if there is a demand.

Again, we ask: From where did the skeptics derive their information and on what grounds do they support their argument?

Another concession I’ll grant but one that has no little bearing on design is the format of the shawl. For sure the demand for a larger wider long shawl compelled the Kashmiris to make theirs bigger. But back to the main argument.

These particular European designs of building façades were Gothic in nature ( known as ‘renaissance’ shawl in France) and our knowledge of them is derived solely from a few illustrations in a French publication, ALBUM DU CACHMIRIEN BY F. Chavant, and an exceptional woven example (V&A, no. T.362-1980, see p. 81 of M. L-S). Except for Couder’s Isfahan (Bizantine style, 1834) and his famous ‘Nou Rouz’ (Gothic style, 1839), shawls which have been often found Jacquard woven, Bournbonet and Chambellan&Duché’s Gothic shawl designs are known only extremely rarely. The Isfahan of course is the earliest shawl exhibiting strong architectural elements; and many related shawls – invariably square shawls and almost all from the Couder atelier-are known. Their patterns exhibit an elaborate baroque style leaning more towards ecclesiastic Byzantium and far removed from any of the known bizarre (Sikh) patterns coming out of India.

In my forty years as a Kashmir shawl dealer half of which were spent living in Paris and my constant travels throughout Europe and India and my frequent contact with the best collections in the world as well as buying and selling thousands of fine pieces, I have never seen a Kashmir shawl pattern based on any of the architectonic French models. And the reason for this? NO EUROPEAN DEMAND. Monique Lèvi-Strauss herself admits that the vogue for these ‘renaissance’ shawls was short lived.

Furthermore, on the flip side, I have never seen any European shawl exhibiting the Sikh motifs in question indigenous to Kashmir of this period, except for those which were exact duplicates –of which many can be found- of those kani woven in Kashmir. The skeptics contend furthermore that since none of these bizarre patterns can be found in contemporary painting, either in India or in Europe, the source of their design must have come from abroad and not India. It’s true that there’s not one known Indian painting that illustrates a Sikh shawl. But this cannot be taken as a measure of its lack of popularity. The Hungarian painter, August Schoefft, in his monumental painting of the court durbar of Maharaja Runjit Singh illustrates very clearly two long Sikh Kashmir shawls employed a curtains in this highly animated scene. Indian artists were not likely to paint a strange new fashion, one insular to a region cut off from the rest of India. Let me point out one important thing. The Sikh designs we are talking about here represent a an extremely narrow segment of a shawl industry known for a seemingly boundless repertoire of shawl designs. One might describe it as a very special artistic movement, albeit short lived, but perhaps not unlike the movements of Cubism or fauvism, both of which had only brief periods of popularity. And like these French movements, the Sikh movement also had its impact on future shawl style.

There are not that many archival sources or references to French patterns of the early 19th century. Besides Couder’s 1823 sketch of a long shawl that shows the seminal beginnings of a miner architectural device such as the running pattern around the shawl’s center field, of tiny mihrabs, there are also the sketches to be found in Chavant’s publications of shawl designs wherein we find a Gothic design done in pashmina by the manufacturer Bournbonet and another one exhibiting a type of Byzantine architecture layered with an overall feeling of Chinoiserie. Both shawls had been exhibited at the Exposition des produits de l’industrie Francaise of 1839.

Monique Lévi-Strauss’ book, illustrates from “Souvenir de l’Exposition de 1839” from the shawl manufacturers Chambellan and Duché, a quarter section sketch of a square shawl, half painted in, of what is clearly and stylistically an already sophisticated Sikh pattern (p166) drawn directly from an imported Kashmir shawl.From the same album, Frédéric Hébert & Co, shows stylistically, a very similar pattern (p207), though featuring a peacock. Not only were both patterns obviously taken directly from Indian shawls, but Lévi-Strauss points out herself (p202) that “The only Hébert design not inspired by Indian models was the shawl known as The Dendera. And this is quite true of just about all shawl manufacturers who had to satisfy an extremely demanding market where competition was fierce. Fashion conscious clients would not accept anything that wasn’t truly Indian in style or nature.

Now the question arises: Did the French have agents stationed in Kashmir, at the ready, to capture such patterns in kani weaving for the French market? And if they did why is it that no such shawls (either Byzantine or Gothic in style) have ever been found in the market? I have yet to come across a kani shawl exhibiting any such pattern.

It is possible to speculate that the Kashmiri weavers, having seen such Baroque European shawls with their fancy architectural devices, scratched their heads and decided that this was too bizarre, instead they set about doing their own cultural thing and taking ideas from their homeland, the Punjab, the Sikh Brotherhood, the Khalsa, etc.

The Sikh Punjab was not part of India. It was an autonomous region rule by a great Maharaja. The region did not follow in the footsteps of an India which was not yet a nation!

My belief is that these patterns were the creative and exclusive products of a group of very talented Kashmiri/Punjabi artists who drew their inspiration from their own culture, their land, their religion, where they lived and the social environment that formed their outlook on life. The list of items mentioned above all point to this.

I invite comments to this essay.

Please go to “Contact” on the main menu.

====================================================================================================

Three of the evites to my previous talks in India during the months of Feb and March, 2014:

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A Note on Understanding Sikh Shawl Construction

Recently a knowledgeable client of mine requested some not-so-often-asked-for details of an interesting Sikh period long shawl I have ( see no. 163 under Kashmiri Shawls). To find the answers, which I must admit baffled me at the time, required some serious hands and knees investigation into the exact piecing of the shawl. Close inspection of the fringes revealed something remarkable which I hadn’t seen on any other shawl. In my ‘fringe’ experience over the past 35 years I’ve always seen the classic solid-color tabs of the Sikh shawl sewn on to the pallus of the kani weave. However, here I discovered a very unusual, if not exciting anomaly: each of the tab colors had been inserted as an extension of the weave. If you’ve ever lent serious attention to many of the seamed classic Napoleonic period dochallas, or long plain-field shawls that were popular until about 1830 you’ll often see how they were ‘invisibly’ pieced together by enmeshing the warps of one half with the other. It’s an absolute miracle how this was done; today, a lost art. This is the exactly the same process employed in attaching these tabs.

Another question had me comparing the piecing of one end (pallu) of the shawl to the end. One side was 3 inches shorter that the other with Paisley heights differing by 2 inches. But overall of course the shawl otherwise doesn’t in the least appear unbalanced since any difference was made up by the sizes of the two kani panels comprising the pallus, which measure approx. 12 and 24 inches each. So how many pieces of kani shawl did the rafugar actually get before he pieced the whole thing together?

The center woven with its ‘door’ or edge-running pattern is one;

The long-running side pieces flanking the center maketwo;

The two kani panels making up the pallus at each end but each composed of two panels ‘meshed’ together, make seven;

And the twolong hashias (with white silk warps).

Nine kani-woven pieces altogether not counting the plain woven fringe tabs. This should be the right count for finely woven Sikh period shawls. One should bare in mind that Sikh shawls predate the patchwork kani products by at least a generation. However, there is another very fine type of High Sikh period long shawl where the panel at one end is woven entirely in one piece on the loom. It extends from the fringe tabs right up to dhoor or central panel. You would think that the other end would have been woven exactly the same but no. It’s woven in two pieces and ‘enmeshed’ together seamlessly and invisibly.

Knowing how a shawl is pieced together is of fundamental importance in learning about its manufacture and aesthetic qualities as well, and in the process of studying it along these lines there will invariably be interesting things to discover. I cannot stress how important it is to compare one end of a shawl to the other, noting the use of different colored threads, variations in design and rarely but sometimes a completely different flower might show up.

This goes for all shawls be they Mughal, Afghan, Sikh or Dogra. It all boils down to taking a serious look into shawl construction.